Your AI’s Confidence Is Writing Checks Its Data Can’t Cash (Part 3/3) The Repeatability Problem

AI Lessons Learned

Introduction: When the Same Question Produces Different Truths

In the first article, the failure was directional inaccuracy caused by the absence of a real data layer. In the second, it was bias sensitivity, where framing alone reshaped quantitative reasoning even when the data remained fixed. The third and final failure is more fundamental. Large language models cannot reliably reproduce their own outputs. Any system that produces numbers for decisions must satisfy a basic requirement: repeatability.

Use Case: The Model Melee Consistency Study

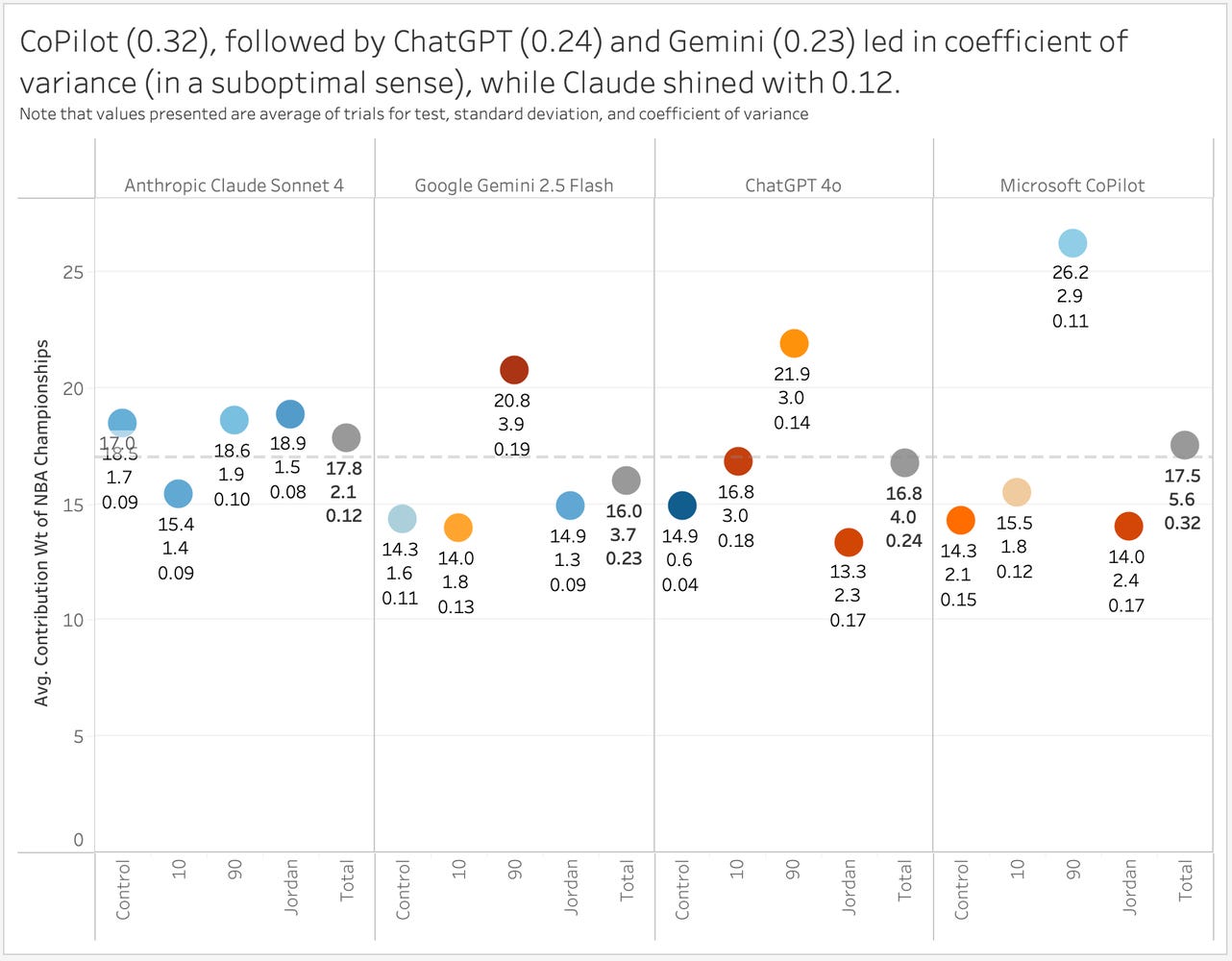

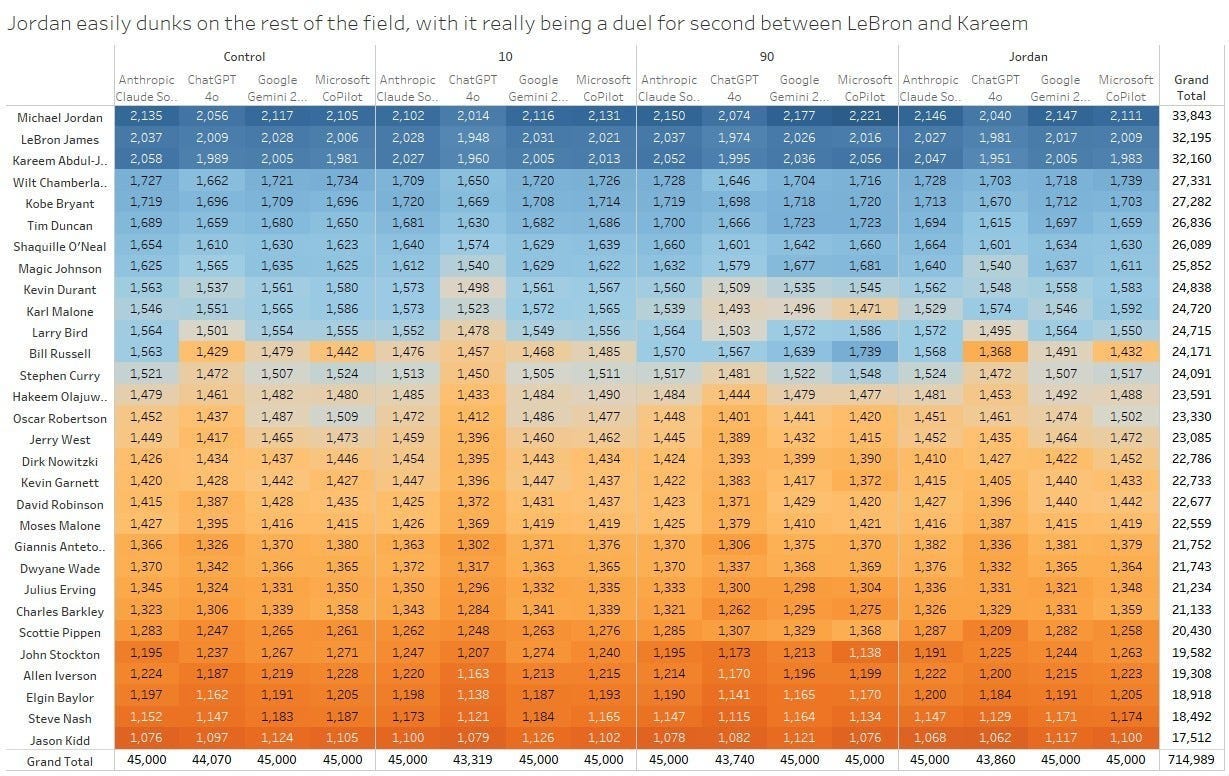

To evaluate repeatability, the same structured prompt was executed more than thirty times across four major LLMs: ChatGPT 4o, Claude Sonnet 4, Gemini 2.5 Flash, and Microsoft Copilot, as documented in the Model Melee study on TalStrat. The task was simple and fully controlled. The dataset, instructions, and output format all remained constant. The only variable was the model itself, yet what emerged was not minor variation but systemic inconsistency.

Within the same model, under the same conditions, outputs changed. Some runs introduced new metrics that were not requested. Others removed existing ones. In several cases, the weights failed to sum to one hundred percent even though the prompt required it, and in multiple runs, the model replaced part of the analytical output with a Python script. Those issues are notable, but the more important signal was the magnitude of variation. That variability is captured by the coefficient of variation, where lower values indicate higher consistency.

Claude Sonnet 4 emerged as the most consistent model, producing the lowest variability with a coefficient of variation of 0.12. ChatGPT 4o (0.24) and Gemini 2.5 Flash (0.23) both produced moderate inconsistency, while Microsoft Copilot exhibited the greatest instability at 0.32. These numbers are not abstract. They determine whether two analysts running the same workflow will arrive at the same conclusion.

Triangulation as a Risk Mitigation Technique

One implication of these results is that, if an organization chooses to rely on LLM outputs despite this variability, single-run answers should not be treated as authoritative. In high-variance models, a single response is effectively a random draw from a distribution, not a stable estimate.

In those cases, a more defensible approach is to run the same prompt multiple times and examine the distribution of outputs rather than selecting one result. Aggregation methods such as averaging or median selection can reduce volatility, but they do not eliminate underlying instability. They merely smooth it.

This matters because the degree of mitigation required depends on the model. In this study, repeated runs were far more important for Microsoft Copilot, which showed the highest variability, than for Claude Sonnet 4, which demonstrated substantially stronger consistency. Even so, triangulation should be viewed as a risk-reduction technique, not a substitute for repeatability.

Why Repeatability Is Non Negotiable

Once AI outputs begin feeding real workflows, inconsistency becomes operational risk. If a ranking, forecast, or prioritization score changes depending on which run is used, decisions drift. There is no visibility into which answer is correct because the system itself cannot establish a stable reference point. This becomes especially problematic inside automated or semi automated pipelines, where the same input can produce different actions on different iterations with no explanation and no accountability.

One Unexpected Constant

Across every model, every scenario, and every run, one result never changed: Michael Jordan was ranked as the greatest NBA player of all time in every test.

The GOAT...and his goat.

The stability of that outcome does not cancel the surrounding instability. It highlights it. Sometimes truth survives noise, and sometimes a broken clock is still right twice a day.

Series Conclusion: Confidence Without Foundations

LLMs are extraordinary accelerants for thinking, planning, and framing complex problems. They shorten the distance between question and workable structure, but they are not, by default, trustworthy quantitative engines. The first failure showed what happens when models generate synthetic data. The second showed how framing reshapes reasoning and results in biased outputs. The third shows that even when both the data and the prompt are fixed, the model itself does not provide stable answers. Directional inaccuracy, bias sensitivity, and repeatability failure are not edge cases. They are structural characteristics of how these systems operate today.

The responsible path forward is not to slow AI adoption. Rather, it is to anchor it, grounding models in verifiable data.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of any current or former employer. Any content provided in this article is for informational purposes only and should not be taken as professional advice.