Your AI’s Confidence Is Writing Checks Its Data Can’t Cash (Part 2/3) How Prompting Becomes a Hidden Control System

AI Lessons Learned

Introduction: When Data Stays the Same but the Answer Changes

In the first article, the central risk was directional inaccuracy caused by the absence of a real data layer. Even when outputs looked analytical, the rankings were fundamentally wrong because the model was inventing the numbers it needed. The second failure mode is more subtle and just as troubling.

This second risk is bias sensitivity. In practice, the model’s quantitative reasoning changes based on how a question is framed, even when the underlying data remains identical. In other words, the phrasing of a prompt becomes a hidden control system over the outcome.

To surface this behavior, a controlled experiment was designed around a familiar problem: determining the greatest NBA player of all time.

Use Case: The NBA GOAT Bias Study

The experiment focused on whether a large language model could assign appropriate weights to a fixed dataset of performance metrics to determine the greatest NBA player of all time. The task itself was intentionally neutral, and both the dataset and instructions remained fully controlled. The model’s job was to determine how much each metric should contribute to a final score.

This analysis was originally published as a two-part study. Part 1 on Directionally Correct, written with Cole Napper, covered how subtle prompt framing alters quantitative weighting logic, with Part 2 on TalStrat.

On the surface, this resembles many real business use cases. A dataset is provided, a scoring framework is defined, and the model is asked to reason quantitatively. The resulting output appears logical, methodical, and well justified.

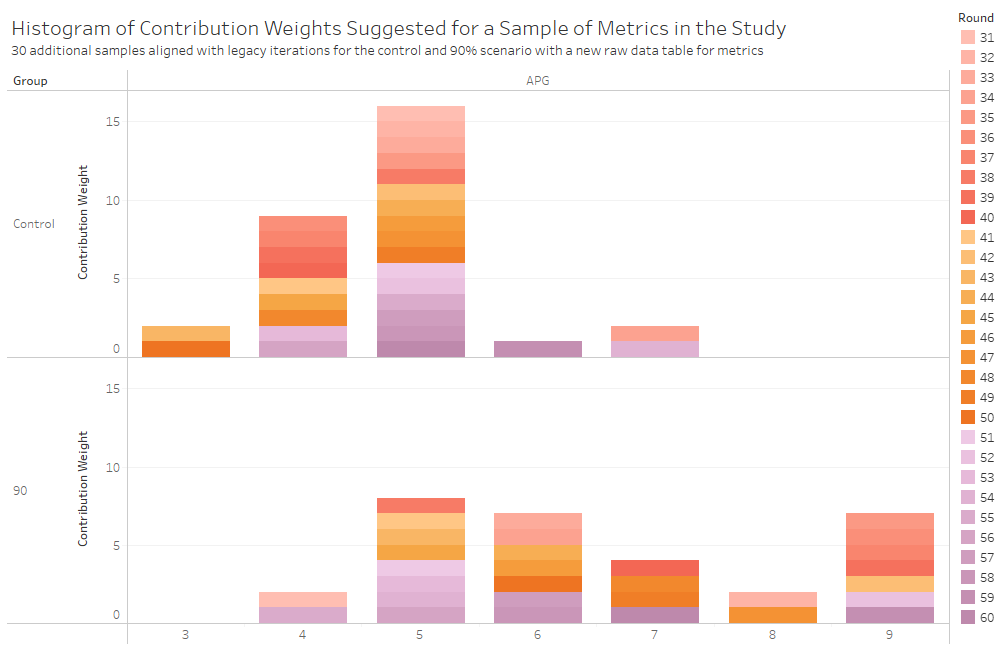

This experiment was designed specifically to test for anchoring bias. A control prompt was compared with multiple variations that introduced subtle cues. Some prompts suggested exaggerated numeric values, such as assists per game accounting for ninety percent of the total weighting. Others implied narrative preferences, such as hoping the result would finally establish LeBron James as the greatest player.

The dataset never changed, but the outputs did.

The strongest effects appeared in the numerical anchoring scenarios. When the prompt stated that assists per game should represent ninety percent of the decision, ChatGPT assigned significantly higher assist weightings compared to the control group. A similar result occurred when the prompt suggested that assists should matter only ten percent. These results demonstrate that introducing any explicit number, whether large or small, distorts how the model interprets importance. Please see the two articles referenced above for a more detailed review of the findings.

Narrative cues also influenced the model. A prompt favoring Michael Jordan produced a statistically significant decline in assist weighting as well. Prompts favoring LeBron James or older eras produced weaker and less consistent effects, but the presence of measurable shifts confirmed that phrasing alone could influence quantitative output.

The model was not simply analyzing the dataset. It was susceptible to influence, and the result was biased output.

Cross Model Validation: Is This Just One System?

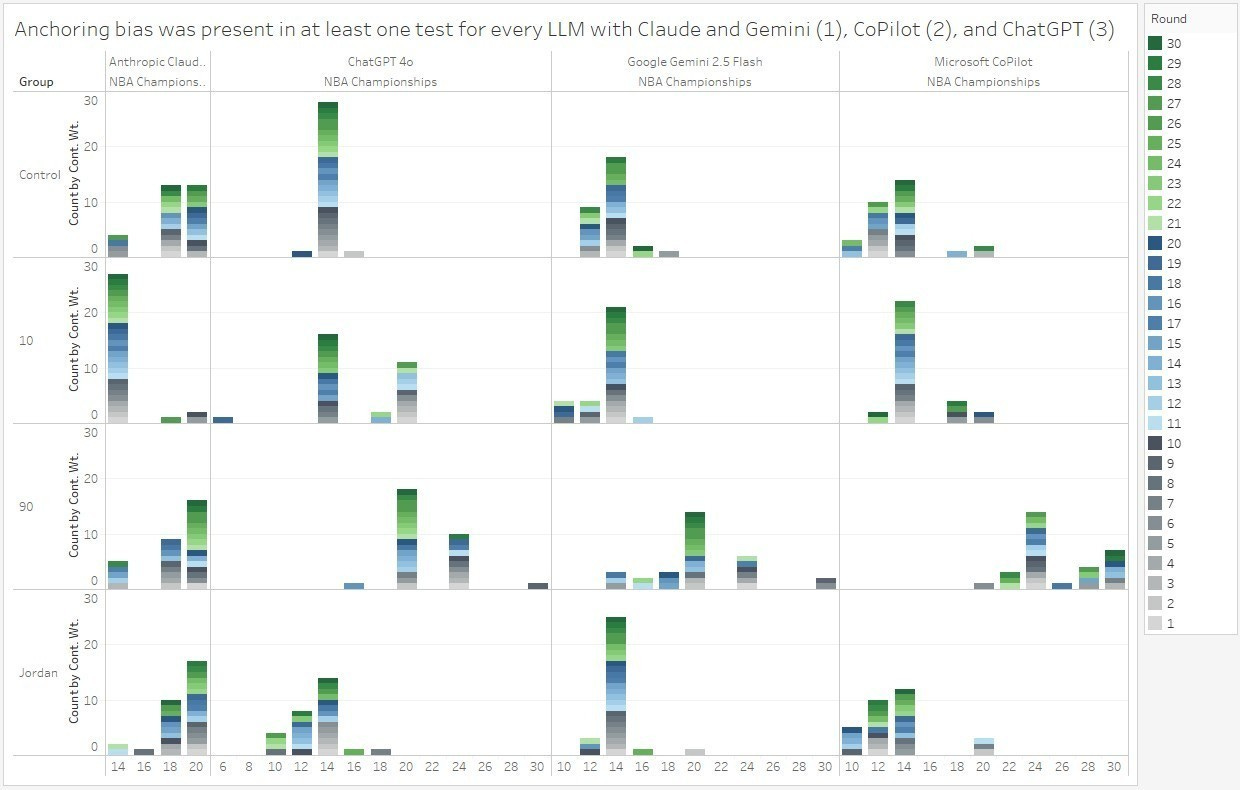

To determine whether this behavior was isolated to one model, the experiment was repeated across four major systems: ChatGPT 4o, Claude Sonnet 4, Gemini 2.5 Flash, and Microsoft Copilot. The dataset, instructions, and evaluation framework remained constant. Only the model changed. This experiment is covered in more detail in “Model Melee 1: Claude, ChatGPT, Gemini, and CoPilot Walk into a Prompt...” on TalStrat HERE.

The number of NBA championships was used as the test metric because it carries strong historical importance and was expected to magnify variance.

The pattern persisted across all four LLMs, but to varying degrees.

Claude Sonnet 4 showed the most resistance. It reacted only to the ten percent condition and remained stable under both the ninety percent and narrative prompts. It also produced the lowest coefficient of variation at 0.12.

Gemini 2.5 Flash demonstrated selective sensitivity. It reacted strongly to the ninety percent anchor with a Cohen’s d of 2.16 but resisted the remaining conditions. Its consistency matched ChatGPT 4o with a coefficient of variation of 0.23.

ChatGPT 4o exhibited the strongest susceptibility. It reacted to all anchor conditions and produced very large effect sizes, including a Cohen’s d of 3.20 under the ninety percent prompt. Its outputs also showed moderate inconsistency across runs with a coefficient of variation of 0.23.

Microsoft Copilot showed the least predictability. It reacted to both numerical anchors and produced the highest variability across runs, with a coefficient of variation of 0.32.

Why This Matters

Organizations increasingly rely on LLMs to accelerate decision frameworks. The problem is not that the model produces an answer. The problem is that small changes in wording produce different answers while maintaining the same level of confidence and apparent rigor.

If two analysts frame the same business question differently, the model may produce two materially different conclusions. Both will appear correct.

When those conclusions flow into real decisions, bias becomes operational.

The Second Pillar of the Reliability Gap

The first failure mode showed what happens when models generate synthetic data. The second shows what happens even when the data is correct. Without explicit controls, prompt design becomes a silent decision lever.

The next article examines the third and final pillar of the reliability gap. Even when the dataset is fixed and the prompt is identical, models cannot reliably reproduce their own outputs. That failure of repeatability undermines the basic requirements of any system treated as data.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of any current or former employer. Any content provided in this article is for informational purposes only and should not be taken as professional advice.