Hiring for Emerging AI Roles Feels Like Playing Tetris with the Wrong Pieces

Talent Acquisition

My dream job after completing my MBA was to be a product manager at Apple. They had quite a few roles that began with "NPI" for "New Product Introduction," and I suspect that I applied for every single one of them for at least two years. I never got an interview and did what any other rationally thinking person would do: I heard that Steve Jobs sometimes responded to external emails, so I sent him one with a few product ideas. Well, I never heard from him either.

The point of this article is to noodle a bit on the issue of skillset mismatches between current and desired jobs, as well as the scenario in reverse. Finding matches on required skills is straightforward when there’s an existing talent pool, like Apple had for product managers. But what happens when you’re trying to fill novel roles, with no obvious pipeline of similar skills to draw from?

Let's dig in, but don't get hung up on exact numbers. The information (percent of the talent pool proficient in each skill and the expected 3-year CAGR) was generated by large language models. Is it perfect? No. It’s directionally correct and useful for highlighting patterns, but for actual hiring or workforce strategy, use robust platforms like LinkedIn Talent Insights, Lightcast, or Draup. Treat this as a conceptual illustration to structure the problem.

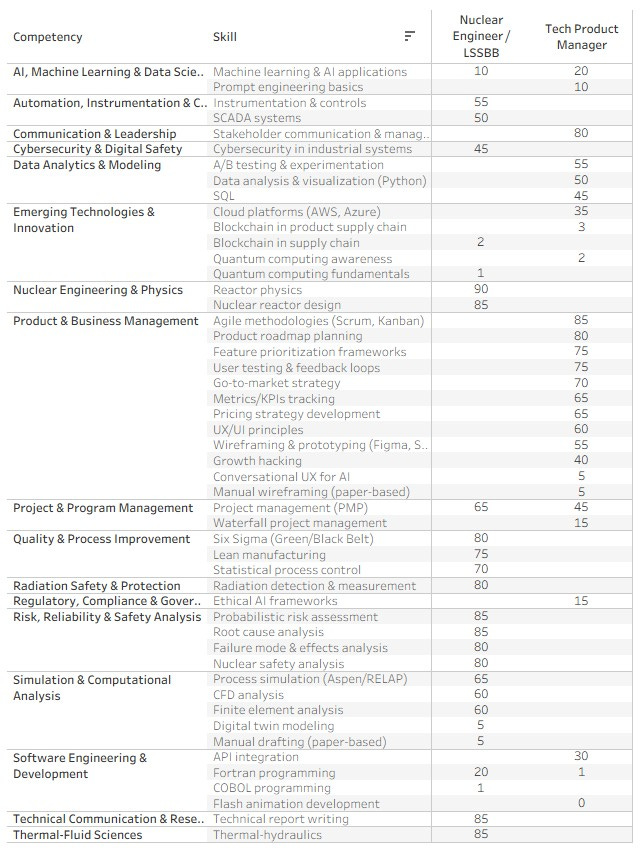

Because ultimately, this isn’t about obsessing over whether it’s 12% or 18% proficient in a particular skill. It’s about understanding that these gaps exist in the first place and thinking critically about how we bridge them in meaningful ways. With that out of the way, let’s take a look at how my skills stacked up against what Apple was looking for back then. I had two roles on my resume: nuclear engineer and process improvement practitioner, vs. what I wanted: product manager in tech. You're looking at two very different roles.

My job simply didn't have many transferable skills to the job I wanted.

Why This Story Matters

This story isn’t just about me and Apple. It’s about how companies think about talent overall. When you’re hiring for a role that’s been around for decades, let's say, a software engineer, financial analyst, or HR business partner, there’s an established talent pool out there. You can write out a job description with required skills and experiences, and you’ll likely find candidates who match them directly, often with a strong pipeline.

But what happens when you’re trying to fill roles that didn’t even exist a few years ago, or yet at all? When there isn’t a stack of resumes filled with people who have “done this exact thing before,” your approach has to change.

We're about to face a challenge as new AI-related roles emerge that have no precedent with titles like: AI Behavior Architect, Prompt Engineer, AI UX Designer, Simulation Engineer, Behavioral Data Scientist, Game Designer (AI/NPC Logic), and AI Policy & Ethics Consultant. There might be a stack of resumes, but none will meet the minimum requirements. Side note: I also reserve the right to make fun of anyone putting out a requisition requiring five years of experience for a role that was just born yesterday.

Cosine Similarity

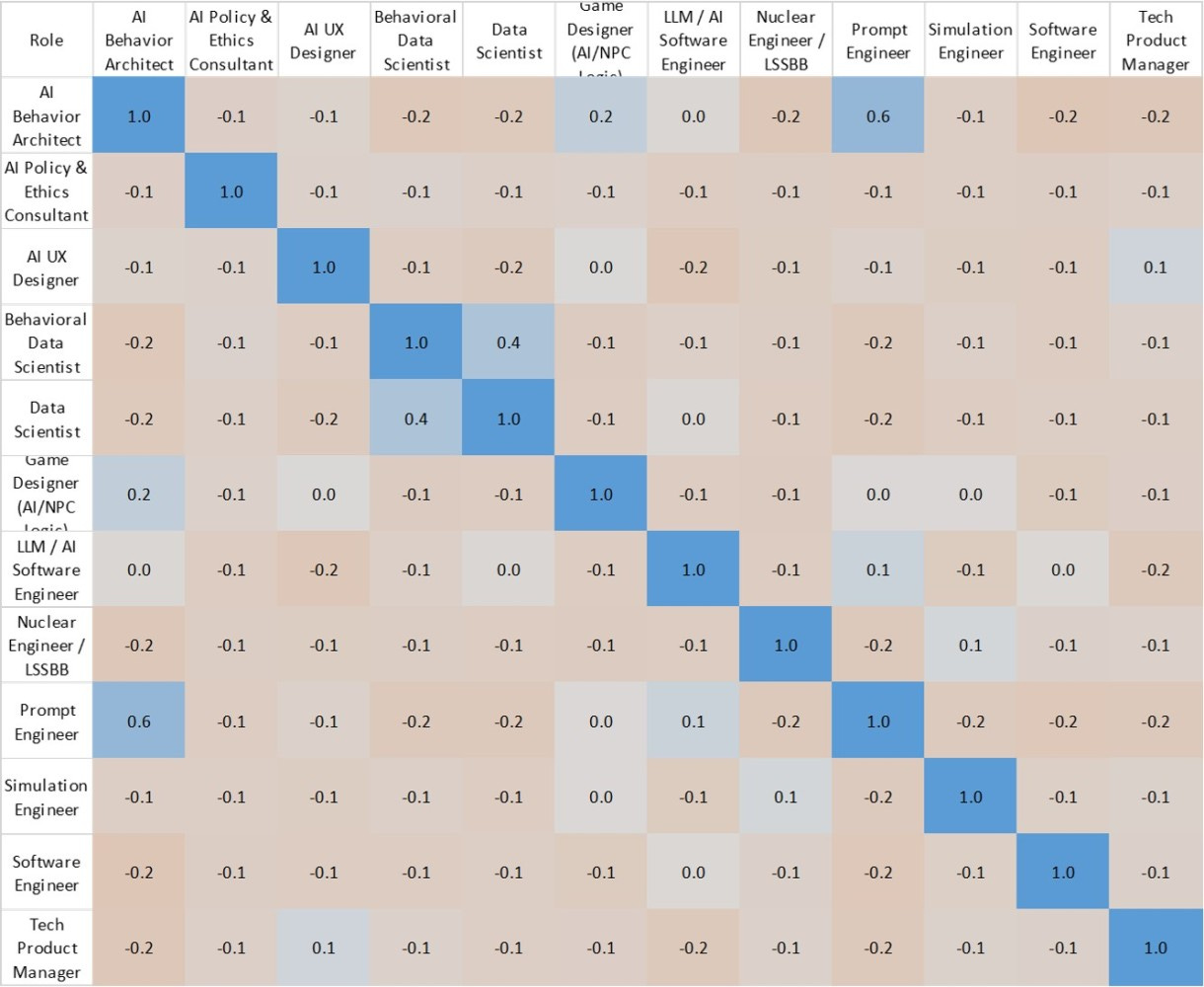

To compare roles, I opted for cosine similarity, a simple but effective method. Imagine each role as a vector of skills, each weighted by proficiency. Cosine similarity measures the angle between them to assess their alignment.

If the value is 1.0, it means the two roles are perfectly aligned in their skill orientation, like a software engineer and a backend developer. If it’s 0, the roles are completely unrelated, with no overlap in skills. And if it’s negative, it means they’re essentially opposites in skill orientation. They don’t just lack overlap; they pull in entirely different directions.

I pulled in all of the roles mentioned thus far into the pot. When I compared myself as a nuclear engineer / LSS black belt to the product manager role I wanted at Apple, the cosine similarity was -0.1 (see figure below). In other words, not only did I not match the skills needed, but my emphasis was pointed almost directly away from where Apple needed their product managers to be.

My accumulated skills and experiences were built for a different purpose. Reactor support and process improvement don’t translate well to user journey mapping or monetization strategy. At a fundamental level, I was solving different kinds of problems with different tools, for different stakeholders, in different contexts. You can see this lack of alignment in Figure 2 below, where the skills of nuclear engineering and product management point in nearly opposite directions on the cosine similarity map.

When you look beyond my oddball mismatch and at the alignment between existing technical roles, such as data scientist, LLM/AI software engineer, and software engineer, against these emerging AI jobs, the results suggest a talent gap on the horizon. You might assume that these current tech-heavy roles would naturally pipeline into the new AI-related ones, as least to some degree. But in reality, the cosine similarities were often near zero or even negative, indicating little to no meaningful overlap in skill orientation.

In simpler terms, even some of our most sophisticated technical talent pools today aren't decent pipelines for these future roles. It’s like having a team full of elite chess players but needing someone who can play Go, related in principle, but requiring fundamentally different strategies, mental models, and approaches. This underscores that the talent gap ahead isn’t just a generalist-to-specialist problem; it’s a shift into entirely new cognitive and technical domains that don’t yet exist in current job architectures.

Quick rabbit role: If you haven't seen the movie Knives Out, please watch it. And, you're welcome. The characters in this scene are about to start a game of Go.

Competency Mapping

I wanted to find a way to make the data more meaningful. Skill-level comparisons are incredibly granular. They tell you whether someone knows specific programming languages, frameworks, or technical tools, but they can also exaggerate differences when the underlying abilities are related at least to some degree.

If we can accept that using skills is overfitting, it is reasonable to map skills into broader competencies. For example, instead of comparing SQL and Python as separate skills, I mapped them both into a “programming” competency. Instead of treating UX writing and user journey mapping as totally distinct, I grouped them under a “user experience design” competency. The idea was to focus on where a role’s abilities gravitate, rather than the exact tools or certifications someone happens to list on their resume.

Figure 3 shows that, compared to Figure 2, grouping skills into broader competencies increases the concentration of blue values, indicating more positive alignment overall. However, while this broader mapping slightly improves similarity scores, major capability gaps remain. Even at a competency level, the fit between existing roles and emerging AI roles persists. At the end of the day, even if the pieces fit a little better, it still isn’t the right gameboard.

Backtracking to my first rabbit hole, did this make me any more attractive as a candidate for that Apple job? No. The similarity got worse, dropping to -0.2. Oh well.

This shows that even grouping by competencies doesn’t magically solve talent fit problems; it simply reframes the conversation companies must have about training, redesigning roles, and redefining qualifications.

Implications for Talent Acquisition

This brings us to the real challenge for companies and talent teams today.

When you’re hiring for a well-established role, it’s like working from a recipe. You know the ingredients, you know the method, and while execution can vary, you have a pretty clear sense of what a successful outcome looks like. But with these emerging AI roles, it’s more like trying to cook a dish you’ve never tasted with ingredients you’re only vaguely familiar with, and you’re expected to serve it to a full restaurant by dinner.

Here’s what that means in practice:

1/ Unqualified Hires: Companies need to mitigate the risk of unqualified hires by defining clear benchmarks for what good looks like, so they don’t onboard people who claim expertise without the depth needed to drive outcomes responsibly or effectively.

2/ Pipeline Problem: Recognize that traditional recruiting channels won’t surface these candidates. Talent teams should assess for adjacent competencies and capability orientation, creating pathways to grow into these roles rather than expecting direct experience.

3/ Upskilling Imperative: Companies waiting for a perfect candidate will be waiting indefinitely. The strategic move is to invest in structured upskilling programs, aligning learning pathways to emerging job architectures and building rotational or apprenticeship opportunities to expose employees to these new fields.

4/ Rethink Qualifications: Titles, years of experience, and traditional credentials are becoming less reliable signals for emerging roles. Learning agility, adaptability, and the ability to operate in ambiguity will be the differentiators because, for jobs with no history, the person who can define the future is often more valuable than the one who claims to have done it already.

If companies don’t address these challenges head-on, they’ll face the same mismatch I did trying to join Apple, except this time, it won’t just be one rejected candidate; it will be entire strategic capabilities left unstaffed, or worse, staffed by people unequipped to lead them.

Thanks for reading!

-Scott

And of course, a quick plug for a side project I built for my kids. It’s a daily news summary that pulls from liberal, conservative, and moderate sources, highlighting where they agree and where they diverge, all in a quick, 3-minute read. Check it out and stay informed from every angle.

Let’s keep the conversation going and explore how we can collectively prepare for and shape the future of work. Your feedback and insights are invaluable. Please like, comment, and let’s keep these ideas flowing!

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of any current or former employer. Any content provided in this article is for informational purposes only and should not be taken as professional advice.

#WorkforcePlanning #Upskilling #FutureOfWork #PeopleAnalytics #SkillsStrategy #TalentManagement #Reskilling #CareerDevelopment #EmergingTech